UN Global Digital Compact – A vehicle for Democracy or Authoritarianism?

Christoph Müller

Christoph Müller

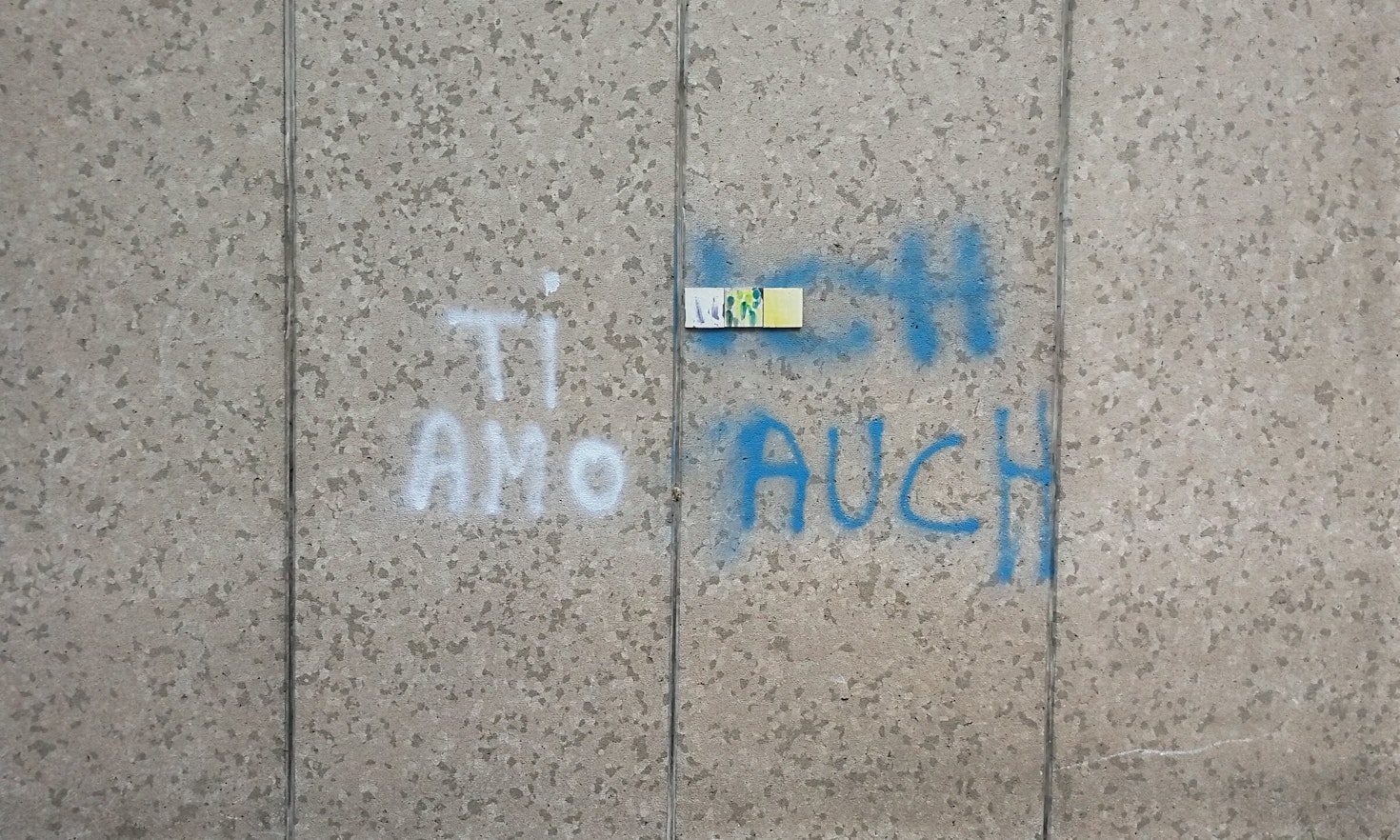

If one happens to think of similarities between the Swiss city of Fribourg and the Italian city of Bolzano/Bozen – as I do, coming from the former and spending a summer in the latter – one might first think of the mountains which surround the two cities. Or perhaps of the rivers which run through them. But most likely, one will think of the languages spoken – one thinks of bilingualism. And indeed, the parallels in this respect are striking, already in terms of numbers: two thirds of the urban population speak French in Fribourg, respectively Italian in Bolzano/Bozen, compared to one third speaking German – that is to say; a dialect of German which is hard to understand for anyone who is not originally from that area – whereas in the whole of the canton of Fribourg, as well as in the province of Bolzano/ Bozen, South Tyrol, the majority-minority proportion is turned around; in the countryside, slightly more than two thirds are German speaking.

The legal situation of the languages spoken in the two cities is also similar: in the canton of Fribourg, both German and French count as official languages, according to the cantonal constitution (art. 6), whereas in South Tyrol German is equal to Italian in accordance with the statute of autonomy (art. 99).

Without any doubt, both cities are immeasurably enriched by bilingualism and home to a multitude of people who, in the same breath, can switch from one language to the other and who embrace the diversity. However, both in Fribourg as well in Bolzano/Bozen, bilingualism also causes tensions, which are – again – not so different from one another. Bilingual education, for instance, remains a controversial issue as well as the region’s toponyms (or place names), a never-ending topic of discussions and newspaper articles in both Fribourg and South Tyrol as well as this the fear of loss of one’s cultural identity and heritage and the fear of marginalisation is present in all linguistic groups.

These parallels are surprising, given the fact that the historic development of bilingualism in the two cities could hardly be more different. In Fribourg, the two language communities have been living with and next to each other for centuries and its bilingualism was conditioned by the city’s position on the ‘Röstigraben’ – an imaginary barrier which separates the German speaking part of Switzerland where Rösti, a dish of fried potatoes is eaten, from the French speaking part, where it is not. Throughout the ages, Burgundy and the Swabian House of Zähringen as well as Savoy and Bern fought to dominate the town and thus both French and German took turns in being Fribourg’s predominant language. For centuries, it was the latter that was spoken by the ruling classes and many rich families decided to ‘germanise’ their names: Bourquinet became Burgknecht, Cugniet became Weck and Dupasquier was translated to Von der Weid. Yet, there are no records of oppression and discrimination of the language which was not the one of ruling class of the time. On the contrary! When Latin ceased to be the language used for correspondence and trade, both French and German became the official languages and during the Middle Ages it is presumed that the statesmen, clerks, merchants, and innkeepers living in and around Fribourg were all bilingual. In the old part of the city, where immigrants from both the French and the German speaking rural areas lived together, a new language developed over the years: Boltz, a dialect born out of the fusion of the ‘Senslerdütsch’, a Swiss German dialect spoken in the countryside of the canton of Fribourg and ‘Patois’, a version of French spoken in the French countryside of the canton. So, for a long time, German and French speakers lived together peacefully.

Language proved to be a divisive force in Fribourg for the first time during the First World War. The German speaking community – which had by the time become a minority in the city – was supported by a pan-Germanic journal called ‘Stimmen aus der deutschen Schweiz’ (Voices from German Switzerland) whereas the French speakers declared their sympathies for the ‘Entente’. Then again, in the 1950s, the harmony began to crumble and both language groups started to be wary of the other. Throughout Switzerland, the French speaking community expressed fears of being ‘germanised’ by the rest of the country, a fear which also spread to the canton of Fribourg, where, in contrast it was the German speaking community who felt more and more marginalised in the city. And indeed, the number of French-speakers rose rapidly in the second half of the century, mostly due to high numbers of immigrants from Italy and Portugal and countries from North and West Africa which found it easier to integrate in the French speaking community. Today, bilingualism in Fribourg has not been neglected, but neither is it actively being promoted, and often it seems as if this historic legacy was a burden, complicating administrative matters rather than a precious contribution to the cultural richness of Fribourg.

In Bolzano/ Bozen, bilingualism came about quite differently. Being located on an important trade-route, the region has always been in touch with many languages, however, German was the predominant language until, through population resettlement programs and a brutal oppression of the region’s German speakers, the fascist dictature tried to create a purely Italian speaking society in South Tyrol. However, after decades of work and negotiations, the province of Bolzano, South Tyrol succeeded to guarantee the legal protection and equality of the German language and today, bilingualism in Bolzano/ Bozen is actively lived and established, especially within the younger generations, although, in many cases, the languages keep being spoken in separate bubbles.

It becomes clear that the historical development of bilingualism in the two cities could barely be more different and yet, today, the situations are so very much alike. Can we suppose, then, that how bilingualism is being lived in the present depends more on the attitude and actions of the people and institutions, rather than on how it developed? That the relations between language groups can deteriorate and become tense in a city where bilingualism evolved organically and worked well for centuries, just as a bilingualism which was born in a setting of violence can flourish and lead to peaceful cultural diversity? I certainly would not go as far as to say that bilingualism can be separated from its history, yet neither do I believe that it is determined by it. It is up to everyone who has the opportunity, or the privilege, as I did would say, to live in a multilingual society, to ensure that bilingualism – which is after all something dynamic and alive, a process, rather than a state of things – does not become something frightful and oppressive that is linked to injustices of the past, but rather a way of living with one another in mutual respect and understanding today.

|

Antilia Wyss is an undergraduate student for Sociology, Russian and Comparative Literature at the London School of Economics. Her special interests lay in the interstice of language and social sciences; sociolinguistics, the performative power of speech and the role of art and literature in social movements. When she is not reading a novel on a park bench or in a café, she likes to go running, cycling, swimming, and snowboarding. |

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license except for third-party materials or where otherwise noted.