The Democratic Memory Act: Spain tackles its past once again

Aspen Brooks

Aspen Brooks

On July 6th, 2021 the French senate blocked the possibility of holding a referendum on whether to enshrine the fight against climate change in its Constitution. President Macron promised the referendum would put into effect the proposals developed and advanced by Citizens’ Convention on Climate which launched in October 2019.

In spite of the partial failure marked by the Senate's stop to the referendum, it is worth considering the way in which France has elaborated and applied an instrument of its so-called Democratic Innovations (Elstub and Escobar 2019, 11–31, 28), namely the Climate Citizens’ Convention which was instigated in order to involve citizens in discussions and deliberations on how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% by 2030, since in the near future, citizens involvement in policy-making will be inceasingly needed, especially on an issue that is confronting the future of humanity as closely as climate change. The idea of setting up a participatory body in order to address the climate crisis was one of the outputs of the Grand Debat National established to channel the strong protests put forward by the so-called gilet jaune in 2018 into the context of an open debate and to identify solutions agreed between the gilet jaune movement and the national government. The French experiment employed what is commonly known in the literature as a “mini-public” (Smith, 2012) , i.e. a panel composed of randomly selected citizens that, over the course of several weeks or months, is granted with the task of analyzing and deliberating on a specific policy question, such as – in this case – how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Generally, the goal of a mini-public is to come up with policy recommendations to be then transmitted to the decision-makers who will then choose if it is appropriate to take them into consideration while drafting acts and regulations.

The French Climate Citizens’ Convention is to all intents and purposes a mini-public, since it was made up of 150 randomly selected citizens, chosen by direct call, out of a total of 255 thousand telephone numbers selected in all French regions, including those overseas and representing all age groups and socio-professional categories. Out of all that were contacted, 30% directly accepted the invitation, 35% said they were interested and another 35% declined the invitation. The government supplied transportation, lodging, meals, babysitting services as well as a daily attendance allowance to all participants so as to incentivize all those that were contacted to take part in the Convention. Besides the 150, selected by lot and the official members of the Convention, a complex governance structure was set up in order to assure neutrality and impartiality to the process. Several technical and legal experts as well as experts in participatory and deliberative democracy composed the so-called “governance committee” entitled with the task of offering help and support to the works of the Convention along every step of the process. Also, three independent guarantors were appointed to ensure that the necessary conditions were met to guarantee the independence of the Citizens' Convention and ensure it could work in suitable conditions.

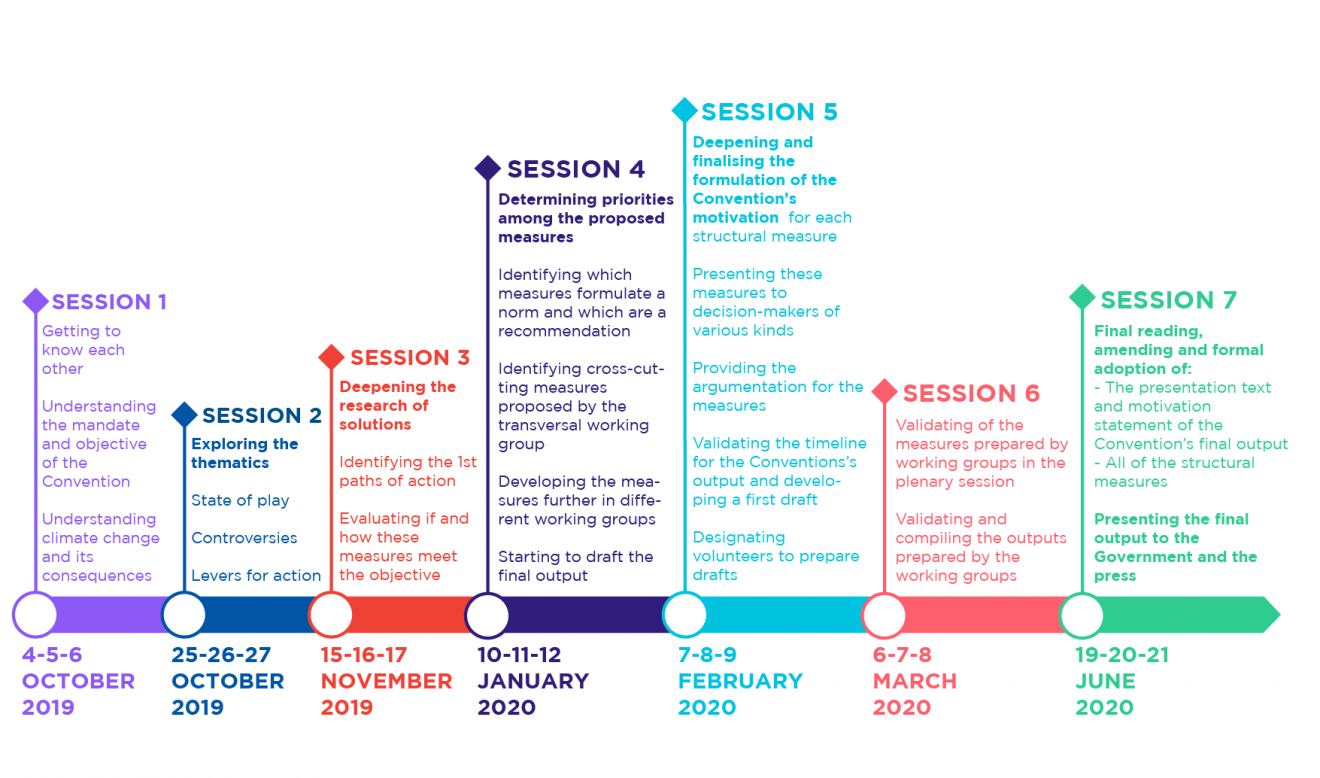

The Convention organized its works over seven sessions: the first two were set up to enable acquaintance among the participants as well as an understanding of the mandate; the third, fourth and fifth were focused on deeper investigation of the issues at stake and entailed collaboration with experts and an elaboration of concrete policy measures; and the last two sessions saw the validation of the results and a presentation of the outcomes to the government and the press (see picture below). Of course, the pandemic also affected this process, particularly with regard to the way in which the Convention members were able to meet. In fact, as of March 2020, the 150 members of the assembly had to stop meeting in person and move to virtual meetings.

Source: https://www.conventioncitoyennepourleclimat.fr/en/

A highly contested aspect of Democratic Innovations has to do with the effects of the processes of mini-publics on the policymaking. It is often said in the literature that these are interesting and important democratic experiments but ones that almost never arrive at the expected outcomes in real-life, given the consultative effects they are entrusted with (Papadopoulos, Warin, 2007). Interestingly, in the case of the Citizens’ Convention on Climate, in order to avoid this dysfunctionality, in a public statement president Macron pledged to transform the results of the convention's work into legislative and regulatory acts. As it is possible to read on the official webpage of the Convention: “On 25 April 2019, the President of the Republic committed himself to submitting the proposals of the citizens of the Convention “without a filter” either to a referendum, to a vote in parliament or for direct regulatory implementation”. The conclusions of the Convention were actually translated into the referendum on whether to include the fight against climate change in the Constitution. Although the commitment of President Macron was kept; the Senate blocked the referendum yet another instance of an innovative democratic process not managing to translate its outputs into real politics.

Elstub Stephen and Escobar Oliver. 2019. “Defining and typologising democratic innovations.” In Elstub Stephen and Escobar Oliver,Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, Elgar publishing;

Papadopoulos Yannis and Philippe Warin. 2007. “Are innovative, participatory and deliberative procedures in policy making democratic and effective?”. In European Journal of Political Research 46: 445–72;

Smith Graham, 2012. "Deliberative democracy and mini-publics". In Geissel Brigitte and Newton Kenneth, Evaluating democratic innovations. Curing the democratic malaise, Routledge.

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.